As a strength and conditioning coach with over 20 years experience, I’ve worked with athletes in numerous sports. Over the years I’ve noticed a hierarchy of which sports’ athletes are the most and least enthusiastic to participate in strength training. In general, athletes from team sports are the most excited with football and basketball leading the way. Lagging far behind are the athletes who participate in individual endurance sports including triathletes, runners, and the toughest of all, swimmers.

Much of the disparity results from the different characteristics of each sport, i.e., football and basketball are full contact sports with football being better described as a collision sport. Both football and basketball require repeated explosive maneuvers followed by periods of recovery. The explosive nature of football and basketball require larger muscles trained to contract quickly, often against an external load. Then there’s the obvious benefit of developing more mass. An offensive lineman weighing in at 350 pounds who is quick on his feet is usually going to beat the 290-pound defensive end. By contrast, swimmers are primarily concerned with setting and maintaining a steady pace, and if there is one concern that I have heard from swimmers, usually women, it’s that they do not want to get “bulky.”

But the benefits of strength training extend well beyond bulking up. The right resistance training program can increase strength without packing on much additional muscle mass, and stronger muscles move more water, faster. An added bonus is that when you combine endurance and resistance training you can shed a few pounds of fat, and who doesn’t like it when their clothes fit better? But, of all the rewards provided by strength training, the most important is that swimmers who engage in resistance training are less prone to injury, particularly chronic over usage of the shoulders, the most common injury suffered in the sport [1-3]. Now that I’ve made the case for the upside of resistance training for swimmers, we can discuss exactly which exercises to do and what equipment (if any) you will need.

Generally speaking, resistance training has two purposes; 1) to increase the strength of the prime movers, i.e., the muscles that are used the most often in your activity, and 2) to increase the strength of the muscles that act in opposition to the prime movers, we call these the antagonistic muscles. Although swimming is considered a full-body activity by most, it is really an arm-heavy exercise with only about 30% of the propulsive force coming from the legs [4]. The prime movers are the triceps, forearm muscles, pectorals, latissimus dorsi (the big muscles of the upper back), trapezius (the muscles between the shoulder and neck), and the deltoids (the largest muscles of the shoulders).

The most frequent mistake that I see when swimmers train themselves is that they only work on their prime movers and largely ignore their antagonistic muscles. This gives the prime movers a double shot of stimulus (swimming and weights) to get stronger while the antagonistic muscles remain comparatively weak. This leads to stronger, tighter muscles in the upper chest and the front of the shoulders. You can see this in younger swimmers, many of whom have a characteristic slouch/shrug in their posture with the stronger anterior muscles pulling the shoulder forward and upward. The imbalance in strength between the prime movers and the antagonists is the most frequent cause of shoulder injuries in swimmers. That’s why I design my resistance training programs to emphasize strengthening muscles of the back, using roughly a 2:1 ratio of total reps in each workout, i.e., twice as many reps on the back muscles as on the chest and arm muscles.

The next areas of emphasis are the abdominal and side muscles. Most swimmers, particularly those who have not been taught proper technique, look like they are laying on a surfboard, paddling only with their arms as their body stays flat in the water. This method is slow and puts a huge strain on the shoulders. Proper technique requires you to roll side to side, increasing your range of motion and moving some of the strain from the shoulders to the core muscles. To help you visualize the importance of hip rotation in swimming, think of a boxer throwing a jab vs. a full punch. A boxer uses a jab to keep their opponent in punching range without letting them get too close. The power of the jab is relatively small because it all comes from the arm. By contrast, when a boxer throws a knock-out punch they step into it and rotate their body around their central axis. This allows them to put their whole weight behind the punch. Swimming freestyle fast requires the exact same emphasis on using the core muscles to help generate propulsive force. Rotation, rotation, rotation.

Finally, we need to add in a few exercises to strengthen the legs. The prime movers of the freestyle kick are the quads, and to a much lesser extent the calves. But, because the legs only generate 30%, and in most recreational swimmers much less, of the force needed to move through the water, we don’t need to worry about strength imbalances in the legs and we can use a 1:1 ratio of reps between leg extensors (quads) and led flexors (hamstrings).

Before we get into which exercises to do and the number of sets and reps, let’s talk about the three basic ways modalities of resistance training; free weights/machine weights, resistance bands, and body weight exercises. The decision of which (or what combination) of the three methods to use is dependent on personal preference, access to equipment, and budget. I like using all three if I can, but there are several ways to skin that proverbial cat and I leave that decision to you. But keep in mind that body weight exercises can be more challenging than either weights or resistance bands. For example, if I got out to my garage to do some bench press, I can lift any amount of weight between 45-415 pounds. But if I do pushups instead, being that I weigh 260ish pounds, I will be lifting around 170 pounds with each rep. Food for thought.

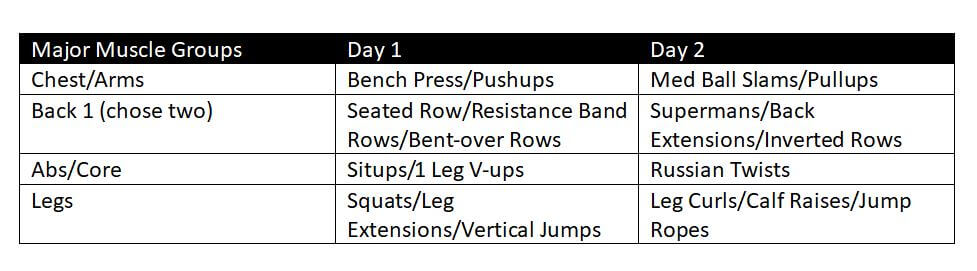

When designing a program, it’s my preference to engage each of the four major muscle groups that we identified (i.e., back, chest, abs, and legs) within each workout instead of dedicating one day to legs and another to chest, etc. I encourage my swimmers to do these exercises twice a week. As for the number of sets, reps, and the weight lifted, we want lots of reps with relatively light weight as we are trying to improve muscular strength and endurance, instead of emphasizing increased muscle size and power. Start by doing between 3-5 sets of 8-12 reps. Start with very light weight that allows you to complete eight reps without difficulty. The next week add another rep and continue this pattern until you get to 12 reps per set. Then drop back down to eight reps while adding 5-10 pounds. After 2-3 of these cycles, change exercises.

For a more extensive list of possible exercises and what equipment to buy please take a look at my two books, Exercise Ain’t Enough, and The Swim Prescription. Below is a table that includes a few exercises that you can find pictures and videos of online.

The last thing I will emphasize is safety. Before starting any fitness routine, you need to check in with your doctor and tell them what you plan to do. Make sure that you have a clean bill of health before getting started. Next, I would strongly encourage you to find a strength coach and have them teach you the basic techniques of each of the movements you want to use in your plan. Doing any one of these lifts improperly can lead to injury. If you cannot afford a few private sessions, invest in some videos that will show you the proper form.

Resistance training is a great addition to any fitness program. Stronger muscles will improve your performance in the pool, help you lose a little weight, and reduce the likelihood of injury. But as with anything related to health, fitness, and wellness, a little investment goes a long way, and you tend to get what you pay for. So, spend a little less on eating out for a month and treat yourself to some high-quality coaching. Now, let’s all done some pullups and swim a 500 for time! Happy swimming everyone.

ALEXANDER HUTCHISON, PH.D., is a fitness and wellness expert in Dallas, TX and the owner of The Athlete Company. The Senior Editor for the journal Advanced Biology, he has experience coachine swimming, water polo, triathlon, marathon, and most recently, strength and conditioning. After completing his master’s degree in Kinesiology at Texas A&M University, Alexander was named the head swimming coach at Austin College. He received his doctorate in Exercise Physiology and Immunology at the University of Houston. He reviews for several journals in exercise science, nutrition, and immunology, and is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. He is the author of Exercise Ain’t Enough: HIIT, Honey, and the Hadza and The Swim Prescription.

References:

- Baker, B.D., S.S. Lapierre, and H. Tanaka, Role of Cross-training in Orthopaedic Injuries and Healthcare Burden in Masters Swimmers. Int J Sports Med, 2019. 40(01): p. 52-56.

- Swanik, K.A., et al., The Effect of Functional Training on the Incidence of Shoulder Pain and Strength in Intercollegiate Swimmers. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 2002. 11(2): p. 140-154.

- Yoma, M., L. Herrington, and T.A. Mackenzie, The Effect of Exercise Therapy Interventions on Shoulder Pain and Musculoskeletal Risk Factors for Shoulder Pain in Competitive Swimmers: A Scoping Review. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 2022. 31(5): p. 617-628.

- Morouço, P.G., et al., Relative Contribution of Arms and Legs in 30 s Fully Tethered Front Crawl Swimming. Biomed Res Int, 2015. 2015: p. 563206.