Exercises for Parkinson’s Disease is the complete guide to achieving better health, providing everything from tips on how to structure your day to take full advantage of higher energy periods, to tailor-made workout programs designed to boost mobility and balance.

Author William Smith, MS, wrote Exercises for Parkinson’s Disease to work as an integrated part of any Parkinson’s disease treatment plan, optimizing mobility, increasing strength and minimizing pain, while providing lifestyle tips to keep you motivated and moving forward. Check out his take on using exercise to benchmark one’s progress.

Parkinson’s disease is a condition that makes basic activities such as walking, navigating inclines & declines, and executing small, sharp turns challenging. The movements involve weight shifting, stopping/starting, coordinating upper/lower body segments, and doing it all while taking in environmental inputs happening all around.

Degenerative conditions present many challenges. In the case of Parkinson’s disease, the condition affects the central nervous system and ultimately its ability to carry out basic functions related to mobility, anatomical functions, and activities of daily living, to cite a few examples. Purposeful activities, such as structured exercise, have been shown to present positive outcomes for those with Parkinson’s disease.

BENCHMARKS

The old adage “if you don’t measure it…”. Not all things need to be measured yet by establishing baselines – subjective and objective – this information may prove useful in providing encouragement and feedback to someone Parkinson’s disease. The key is providing assessments that are easily replicated, applicable to daily life and activities, and most importantly safe. We establish three categories of assessment that cast a wide net, related to Parkinson’s disease.

Our 3 assessment categories are as follows:

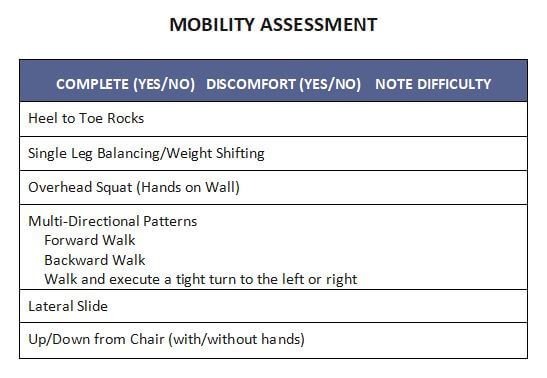

● Mobility

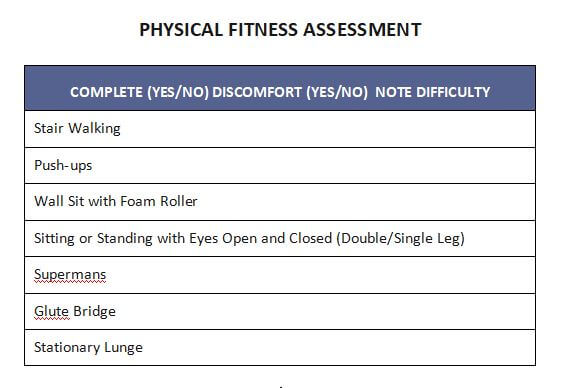

● Physical Fitness

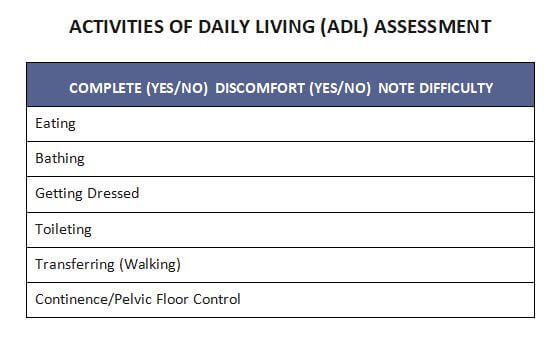

● Activities of Daily Living

#1 Mobility

Mobility is an umbrella term covering flexibility, balance, and general body control. As we age, it’s generally thought that our movement quality decreases due to loss of muscle strength, toning and slow-ing of reflexive response. When movement quality decreases, the likely of losing your balance resulting in a fall goes up. My grandfather, a healthy 92 year old, was out for his daily walk, lost his balance and fell. He passed due to complications from the fall. And while my grandfather didn’t have Parkinson’s he knew that moving his body everyday was vital to maintaining overall wellness.Fortunately, through healthy living movement quality can be maintained, and hopefully at a high level.

#2 Physical Fitness

Physical Fitness is the overall physical work capacity involving exercises that challenge strength and endurance. Exercises utilizing your body weight, resisting gravity (i.e. postural alignment and line of sight), and being able to execute manageable purposeful, strides without loss of balance or body control – the “pushing off” phase of walking is important to note, rather than shuffling.

By assessing your physical fitness with exercises such as pushups, stair walking, lunging, and squatting using large muscles, objective benchmarks can be established for future evaluation. In some instances, more importantly is the subjective feedback. Completing a physical challenge for anyone, especially with a degenerative condition such as Parkison’s, may provide the encouragement to continue investing time and resources into their health.

#3 Activities of Daily Living

Activities of Daily Living, often referred to as ADLs, contain elements of Mobility and Physical Fitness, and are not generally not as physically strenuous as they can be frustrating for someone with Parkinson’s. Incidental tremors, kyphotic (rounded) posture, forward head positioning, and limited range of motion about the shoulder girdle present physically making ADLs more challenging. For example, combing your hair or reaching above your head to grab soup from the cupboard, are more difficulty with limited range of motion around the shoulder girdle. By performing stretching in the front and strengthening in the back, someone could improve their ability to reach above the head with decreased risk of a fall or injury.

ASSESSMENTS

Take your time on the assessments. Your goal should be to complete them in one week’s time. Do them when you are fresh and alert. Possibly first thing in the morning, yet decide that on your own.

For assessments you find challenging, attempt to reassess every 4-6 weeks assuming there’s a strategy in place designed by an exercise specialist that is approved/discussed with your primary care provider and/or neurologist. Practicing the assessments in and of themselves several times per week will contribute towards improvement as well.

Lastly, NEVER feel pain during the assessments. Physical distress is not uncommon, namely elevated respiration or heart rate and acute muscle fatigue. If you have not performed regular physical activity recently it’s prudent to have a check-in with your healthcare provider.

In closing, Parkinson’s disease is a condition that affects many aspects of the human being. The degenerative nature of the disease on the nervous system and ultimately muscle strength and tone creates situations where balance and mobility are more challenging.

By benchmarking your progress with the 3 assessment categories, and establishing an exercise program addressing areas of need, rest assured you’ll be more informed, motivated, and focused on what the next day may bring. Check out my book Exercises for Parkinson’s Disease for more information.

WILLIAM SMITH, MS, NSCA, CSCS, MEPD, completed his B.S. in exercise science at Western Michigan University followed by a master’s degree in education and a post-graduate program at Rutgers University. In 1993, Will began coaching triathletes and working with athletes and post-rehab clientele. Will has advanced specialty certifications in cancer, post-rehab exercise and athletic development.